It has been a while! Enough of that… let’s get into it…

Last year, I was at a place in my life where I could once again dedicate time to the study of martial arts. Like many practitioners, it has been a lifelong journey of learning, trial, and many, many errors. In addition to stepping back into a dojo, a Brazilian Jiu Jitsu gym, and a sunny basketball court, I’ve spent a great deal of time researching history and applications of various martial arts. It borders on obsession.

There are so many good resources, both in print and in video, that showcase the history, culture and effectiveness of classical karate, it is hard to name them all. I’ve reviewed a handful of books (and more to come).

But even with all of this material, knowledge, expertise, and proven effectiveness both in controlled environments like the UFC and in the chaotic circumstances of real-world self defense, karate has a horrible reputation among modern day martial artists and keyboard warriors alike. Why?

Two words: sport, karate.

I tried…

Since coming back to martial arts after about a four year hiatus, and becoming a part of various online communities, I’ve tried to take a very live and let live approach with respect to various we’ll call them “interpretations” of karate. But frankly, I just can’t pretend anymore.

This change of heart culminated about two weeks ago when my son and I competed at a national-level sport karate tournament. I haven’t been to a tournament of this size for nearly 30 years, and obviously, a great deal has changed since then. Prior to this, we also competed in a smaller local tournament, and still made many of the same observations. The difference between the two tournaments? The scale. I’ll get to this in a second.

So what is it about sport “karate” that has me so bothered and why does it matter?

So first thing is first… karate is an Okinawan cultural artifact, and in my opinion, it should be treated as such. As a Westerner, there are many linguistic, historical, cultural and religious undercurrents that lead to the development of karate that I can study but never fully appreciate. There are certain traditions that I can imitate (bowing, wearing a dogi -which is actually Japanese, salutations in kata, etc.) but they are not mine to change or adulterate. Even within the vast amount of room for creative interpretation of kata, techniques, and teaching methods, there are limits to what a non-Okinawan may actually change without some sort of Okinawan acceptance.

Everything about sport “karate” smacks of a cheap mass produced facsimile of the original that strips out the soul of the art in favor of pleasing crowds and making money (kind of like a Disney Star Wars trilogy…). It is hollow, vapid, and utterly devoid of any meaningful traditional, cultural or historical value.

One of the ways to “win” in sport “karate” traditional kata division is to find an obscure kata and mutilate it as much as possible without actually changing the movements. The lady in the video above is performing Go Pei Sho.

Now, contrast the above performance (which received many applause and a won the competitor a grand championship) with the demonstration below (which, by the way, also has an introduction which includes the historical and cultural significance of the kata).

The popularity of sport “karate” has completely overshadowed the practical and cultural value of classical karate just by virtue of the fact that sport “karate” schools pump out blackbelts by the thousands every year. The tournaments are massive, and the financial incentives to hand out flashy prizes and cash awards are vast.

The simple truth of sport “karate” is that it is a money machine machine disguised in “confidence boosting” and “achieving fitness goals” marketing jargon. While it may indeed be a confidence builder and help some people with fitness, it does so at the expense of someone else’s cultural heritage (we’re good at that in the US).

You ain’t seen nothin yet…

If you think the histrionics of the Go Pei Sho performance was bad, we haven’t even discussed the shenanigans with Okinawan and Japanese weapons.

By far, three of the most popular weapons in sport “karate” are bos (staffs), nunchaku, and swords.

Bo and staff performances include all of the obligatory yelling and screaming that one sees with empty hand kata, but now there are props to showcase hand-eye coordination. And to be completely fair, there is an incredible degree of skill involved in the tricks and twirls that one may see. But at what point does it cross the line from a martial art to a dance? Funny you should ask…

Let’s ask the founders of modern karate what they think:

…It is not a dance competition trying to decide who has the most gorgeous display… it is a form of self-defense that can be the difference between life and death.

-Konish Kazuhiro, Excerpt from Mabuni Kenwa’s “Karate Kenpo: The Art of Self-Defense”

Once a kata has been learned, it must be practised repeatedly until it can be applied in an emergency, for knowledge of just the sequence of a kata in karate is useless.

-Funakoshi Gichin

“Kata are not some kind of beautiful competitive dance, but a grand martial art of self-defense, which determines life and death.”

-Mabuni Kenwa

“You may train for a long time, but if you merely move your hands and feet and jump up and down like a puppet, learning karate is not very different from learning a dance. You will never have reached the heart of the matter; you will have failed to grasp the quintessence of karate-do.”

-Funakoshi Gichin (again)

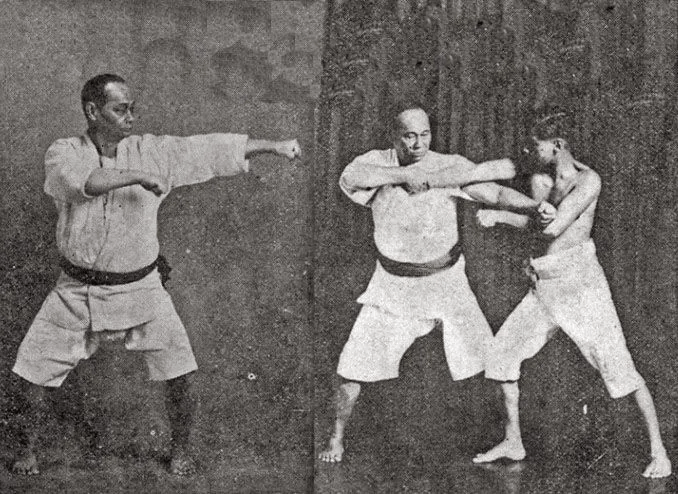

The early Okinawan karate masters were exceptionally pragmatic. According to most available accounts, the primary influence on Okinawan todi came from the Fujian Province in China. While kung fu styles have their own practicality, they also add a bit of flair. That flair is essentially stripped out of todi/karate and we’re left with a simple, utilitarian, and brutal system of self-defense.

In other words, if something didn’t work, or it was just for show, the Okinawans discarded it. The quotes above (of which there are dozens more) only serve to reinforce that point.

So what relationship does bo twirling have to karate? Simply put, it doesn’t. If it does not have current or historical self-defense value, it is not karate. Full stop.

One can easily find the same examples of other watered down Okinawan kobudo weapons such as nunchaku, sai, eiku, kama, or tuifa (tonfa) in sport “karate”, so I won’t belabor the point.

But wait… there’s more

As horrible as the empty hand and Okinawan kobudo sport dances are, it actually gets worse… Yes… seriously.

Let me preface this by saying I am no sword expert. I have a handful of swordsmanship classes under my belt, but I do practice with a live blade. In other words, I train with a sense of paranoia and respect for the weapon in my hands. And frankly, real iaido kata are kind of short, and unless you know what is happening, somewhat boring to watch.

In the clip below, the gentlemen demonstrates what I believe to be good fundamentals. His stances are grounded, he cuts instead of chops, and the techniques demonstrated are legitimate sword techniques (maybe including some of the jumps – I don’t actually know). But let me start the video where things get dicey…

“Traditional” katana division

Notice how the competitor cleans the blood of his imaginary opponent off of his blade using his sleeve? Not only is this impractical, it is dangerous. Sorry… I’m not trying this at home with my live blade.

But hey… it looks cool, and I think it originated from Kill Bill.

Trading pom-poms for belts

If you’ve made it this far, I think you’ve already figured out what I have to say about this.

Wrap-up

So why does any of this matter, and why make a fuss about it?

From an outside perspective, this is not much different than a cheerleading, gymnastics or dance competition. And if it were an one of those things without a disguise, I wouldn’t care.

It matters because fundamentally, karate is for self-defense. Many people start karate (or other martial arts) with a variety of goals (weight loss, confidence, etc.) that include being able to handle oneself in a dicey situation. Sport “karate” does not deliver on self-defense, and as I’ve shown, it teaches poor fundamental that include techniques that can get the practitioner hurt or worse.

Confidence is fine. But being a 3rd degree black belt in bow spinning is not something that can or should give someone the confidence to take on a ruffian who wants to put a knife in their gut (hint: just give them your wallet…). But being disguised and marketed as a “martial art”, many sport “karate” practitioners may have that false confidence that what they do on the dance floor or in the point sparring ring will translate to saving them in a dimly lit parking lot.

Karate, true classical karate, is a legitimate and (potentially) lethal self-defense system. But the majority of “karate” practitioners in the U.S. and other western countries actually participate in militant cheerleading. This is why karate has a horrible reputation… because the majority of karategi-clad screamers aren’t actually practicing karate despite their claims.

What they do is not what we do, and I am actually done being nice about it. I can’t pretend to be okay with labelling something that can easily get a practitioner hurt or killed as “karate” when it has no documented links or roots to karate.

The goal of the Village Karate of Stafford is to join the efforts to restore information that was lost about the traditional Okinawan martial arts and elevate their status legitimate self defense systems that are applicable to our times. In some cases, we can piece together bits of information that is scattered around the world like a bunch of forensic historians. In other cases, we just have to experiment with concepts, just like the forbearers of karate did, and figure out what works (and then ditch the rest).